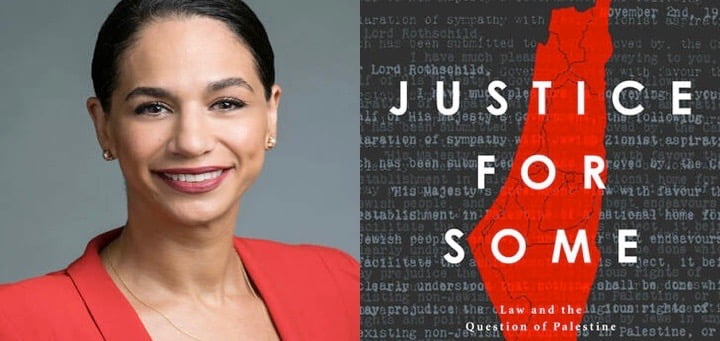

Presentation of the book “Justice for Some” by Noura Erekat

* Hassan Ben Imran

Book information

Justice for Some: Law and the Question of Palestine

Author: Noura Erekat, a US-Palestinian legal researcher in the field of human rights, and an assistant professor at George Mason University in legal and international studies.

Original language: English

Publisher: Stanford University Press

Publication year: 2019

Number of pages: 331 pages

More than seventy years have passed since the declaration of the establishment of Israel and the displacement of the Palestinian people, and more than a century has passed since the fall of Palestine under the British mandate that paved the way for the Zionist movement, leaving the Palestinian people under occupation, without land, state, sovereignty or self-determination. While the Palestinians stand without any support, Israel is living its best moments with blind support from the US, the world’s sole superpower, which has tried to appear to be honest for decades, but – with Trump’s arrival at the White House – It abandoned merely being a behind-the-door support tool for Israel and began to show its plans to the public, where it presented a plan that can only be described as an attempt to end the Palestinian cause forever.

In light of the above, this book – which simulates the author’s experience over 20 years as an international lawyer, activist in the Legal Committee in the US Congress, lecturer in international law, and one of the founders of the Jadaliyya website – comes to discuss the reason that brought the case to this situation, but from a legal standpoint and in a smooth way that allows non-specialists to view the book and benefit from its summary. Perhaps this book will come at an appropriate time in light of the direction of the Prosecutor of the ICC to open an investigation into the crimes committed in the occupied Palestinian territories. The book constitutes an important addition to the debate in the US over attempts to politicize and exert pressure on the judiciary. The book consists of five chapters, in addition to the introduction and the conclusion, in which the author discusses the most important stations with a legal effect in the history of the conflict in a linear, chronological manner, starting with the colonization of Palestine to the present time.

The book stood in its presentation between the idealists who believe that the law is capable of restoring rights and redressing grievances, and among the realists who see the law as mere texts that have no value in the worst cases, or tools that the strong use to defeat the weak. The author discusses the sayings of those who believe that international law – or the international path as some call it – is sufficient to make the Palestinians regain their land – or at least part of it, and those who see the logic of the law as mere surrender, and who believe that the law is not fair at all.

The book stood in its presentation between the idealists who believe that the law is capable of restoring rights and redressing grievances, and among the realists who see the law as mere texts that have no value in the worst cases, or tools that the strong use to defeat the weak.

Also, she reminds us that whoever hears the sounds of bombs that are thrown over the heads of civilians in the Gaza Strip, and then hears the legally supported Israeli justifications for these actions as self-defense, would find it quite challenging to believe that any good will come throughout that path. The author argues that the Palestinian people over many decades lost hope in the international community and its law.

However, the writer’s position becomes clearer throughout the book when she stands at a close distance from the realists, but refuses to surrender to their logic, and sees in accepting it a sort of defeatism that is not acceptable in the case of liberation movements. First, it considers the impartiality of the law – or in its expression, which is repeated throughout the book, whether by declaring or hinting: “Law is politics.” In the end, international law is – in one way or another – the sum of the legalization of the balance of power in a given period.

The author believes that the colonial powers exploited international law – carrying the banners of self-determination for the peoples under Ottoman rule – to colonize them and pass their colonial agendas through the League of Nations. However, the author rejects, at the same time, the idea that the law is necessarily biased, and she thinks that the matter is linked to several factors, one of which is the insistence of the liberation forces and their relentless pursuit to obtain the rights of their people and make the law recognize them. Including the Palestinian case, which forced Britain to issue the White Paper after the Great Revolution (1936-1939), as well as recognition of the Palestine Liberation Organization internationally and its appearance before the United Nations in 1974, and others(1).

Thus, the author appears a realist in her understanding of the law that is not an independent article that is not affected by political tensions, and at the same time, a constructivist in her methodology in dealing with the law. Several examples of this constructivism are cited, such as the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, when the power of the people’s protest and the struggle of African Americans – with their allies – led to the recognition of their rights by American law, and then the success of a black man to be the president of the country after nearly half a century, former US President Barack Obama. Although she believes that the Civil Rights Movement is not over yet, she believes that it is making progress day by day. Another example is the success of the Palestine Liberation Organization in gaining international recognition and addressing the United Nations General Assembly in 1974, to be the first official non-governmental body to address the General Assembly in its history.

However, the author, at the same time, recalls the many other examples in which the law did not help the right holders for reasons that can only be understood politically. She gave an example of this in a case filed by several lawyers at the beginning of the current century before the New York court against Ya’alon, the former defense minister in the Israeli government, and Avi Dichter, the former Minister of Internal Security and the former head of the Shin Bet, after they fulfilled – in a miraculous way – the conditions of admissibility to the court. The court then dropped the case on the pretext that it was non-justifiable. In other words, the court is not the appropriate body to decide the matter, taking into account that Ya’alon and Dichter enjoy immunity. However, what was surprising is – according to the author – that the same court later accepted similar cases against Chinese, Filipino and Serbian officials, among others, although they also enjoyed immunity.

The author also gave many examples – based on her experience as a lawyer and activist in the legal committee in the US Congress – indicating that when it comes to Israel, there are political factors that interfere and prevent justice from taking its course. She concluded that it was politics that drew that path, not the law. Moreover, she reiterates that law is politics.

The author, Noura Erekat, talks about problems related to international law itself, related to the dialectic of implementation. International law is not like domestic law. There is no supreme central court and no international police guarantee the implementation of its rulings. After all, international law depends on the voluntary commitment of states. But at the same time, no one can reduce the pressure that the international law exerts on the states, and this explains why Israel has harnessed enormous capabilities to justify its position legally, and even tamper with the law to prove its narrative. This is something the author believes that Israel has succeeded to a large extent over the past decades.

Between the Balfour Declaration and the establishment of Israel

In a linear, chronological manner, the author begins to discuss how the law was used by the great powers to pass their agendas on oppressed peoples, and how the League of Nations was used as a tool for it. In this context, the author talks about the Balfour Declaration, which has no legal basis in any way, except that it became a legal document enforceable by force after Britain imposed it on the Palestinians through its inclusion in the Mandate deed, despite its violation of the Covenant of the League of Nations.

However, the author at the same time cites examples of the success of the Palestinian struggle – specifically the Great Revolution in the 1930s – in forcing Great Britain to recognize their rights and issue a legal document that is supposed to be legally binding on the British government, by announcing the cessation of Jewish immigration and the establishment of a Palestinian state for everyone in it, under the name of “The white paper”.

A permanent occupation?

With the occupation of the rest of Palestine after the June 1967 war, the author discusses how the law itself helped Israel to legitimize its occupation, as she believes that the law allowed doing so through the provisions relating to the occupying power’s responsibility for the occupied population – as stated in the Fourth Geneva Convention. This enabled Israel to change the parameters of its occupation into a permanent occupation and to entrap the Palestinians to contribute to its legitimacy from where they do not know, through the Oslo agreement.

The author passed through many international resolutions that Israel was able to impose its interpretation on it – or at least to make the international community view its legally flimsy pretenses as significant ones – specifically Resolution 242 and the terms of withdrawal from “all” the occupied territories or “some of them”. The text of the decision, in the English language, demanded that Israel withdraw from territories it occupied after the war, without using the definition “the”, while the French text – official as well – used the definition (des fresoir based ones occupés). This discrepancy gave the lawyers on behalf of Israel an opportunity to manipulate the meaning of the decision and present their interpretation as one of the visions considered in it legally; as they considered that the withdrawal from the lands includes the Sinai desert instead of the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and the Golan Heights. This behavior was present in other resolutions as well, such as United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194 relating to refugees, which Israel tried to make with a humanitarian appearance – after it had failed to impede it – by calling for the establishment of a global fund to aid Israeli refugees that Israel would contribute to its establishment and support, thus getting rid of the direct responsibility of asylum.

The author passed through many international resolutions that Israel was able to impose its interpretation on it – or at least to make the international community view its legally flimsy pretenses as significant ones – specifically Resolution 242 and the terms of withdrawal from “all” the occupied territories or “some of them”

When Israel faced severe criticism from its allies for its annexation of East Jerusalem after the June 1967 war, its ambassador to the UN, Abba Eban, tried to justify this by claiming that this was not an annexation (knowing that the annexation was constitutional in 1980), but rather administrative measures to ensure the smooth functioning of the Jerusalem municipality. However, after the issue of annexation became clear, it began to resort to the aforementioned argument about the generality of the text in Resolution 242.

As usual in all discussions about the feasibility of the law, the author pointed, on the other hand, to a bright example, which is the success of Palestinian militants in gaining international recognition and making the international community see them as freedom fighters after seeing them as rogue terrorists, precisely after Arafat’s speech before the General Assembly of Nations United in 1974, to be the first leader of a non-state entity to address the General Assembly.

Palestinian Versailles Treaty!

Erekat began the chapter on the Oslo agreement with a quote by the late Edward Said describing the Oslo agreement as a Palestinian surrender agreement, describing it as the Palestinian “Versailles” treaty- aimed at the humiliating surrender agreement signed by the Central Powers (the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian and the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Bulgaria) after their defeat in World War I.

The author says that since the 70th, up to the pre-Oslo period, the international position was steadily moving towards recognition of the justice of the Palestinian cause and the justice of Palestinian demands, and the first intifada came to give this trend an additional impetus. The coincidence of the start of the breakdown of the apartheid regime in South Africa had the effect of increasing that impetus.

However, with the start of the Madrid talks and the subsequent signing of the Oslo Accords, it seemed as if the Palestinians had begun to gain their rights, and it appeared later that the conflict was a struggle over details, not an integrated conflict. This was the essence of the Israeli strategy, which worked hard to find loopholes in the legal texts. Specifically, the term “the” the aforementioned definition was mentioned in Resolution 242, and then it began promoting the idea of searching for “practical solutions,” and then codifying it. This is what was stated explicitly about the legal advisor to the Israeli army at the time, “Daniel Reisner”, who said that there were two schools for resolving crises; the first is based on establishing legal rules and then trying to implement them, the second is searching for “practical” solutions, and then after agreeing on it, it must be included in international law by signing the agreement. Perhaps this illustrates the Israeli philosophy based on imposing a fait accompli and then trying to gain international recognition and impose it on the Palestinians to become a law, instead of negotiating with the Palestinians based on rights. This was what US Secretary of State James Baker said that the Palestinians should avoid discussing the law if they want to reach a solution. In conclusion, the agreement was signed by exchanging recognition of the PLO for Palestinian independence – in the words of the author.

But the author then tried to explain why the Palestinians went towards this agreement knowing its bad! You say that everyone knew the bad of the Oslo agreement, so why did the Palestinians turn to it!? And she talks here about the international pressure and regional conditions that made the PLO submit and sign on an agreement that proved, after 25 years, it would not have succeeded in the first place – if we assume the possibility of using the term “success” in this case. The Arab regional order had suffered a blow that had not recovered from it until now with the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and the US invasion of Iraq after that, which led to the loss of Iraq after Egypt’s loss by signing the Camp David Accords, and the international system was disturbed by the dissolution of the Soviet Union, which gave the PLO a margin for maneuver. Despite the steam resulting from the first intifada, however, it made the organization feel “out of the game”, which made it lose the ability to properly invest it.

The author concluded that this agreement – which became a legal basis – was nothing but the result of political pressure in the first place before it was based on Palestinian rights. Indeed, Israel made the Palestinians feel that its recognition of crumbs of their rights was a “concession.” Then she wonders: How did ending the occupation and withdrawing from the occupied territories become a “concession”, even though it is known by international law that this is an inevitable duty of the occupying power!?

From occupying the people to fighting them

The author then goes on to talk about how Israel moved from the occupation of the Palestinian people to direct clashes with them during the first and second intifada, and it continues to do so until today. Instead of carrying out its duties towards the people as an occupying power, we see it using terms such as “self-defense,” even though it is a term associated with aggression, not occupation! So aggression is establishing a state by sending its armed forces to invade a territory that is not affiliated with it without a justifiable reason, while in the Palestinian case, Israel is the occupying party, and its military forces are present on a territory that is not affiliated with it, so how can it claim the right of “self-defense” in a region not affiliated with it!? She inferred through this on how Israel sought to legalize its narrative with the international law and make its claims legally acceptable, and invest in its legal machinery in a way that enables it to create legal arguments – even by relying on legally permissive or anomalous opinions – and promotes them through its negotiators, ambassadors, “academics” and media outlets, in a way that makes its viewpoint either the dominant view or at the very least, makes it a view that “deserves to be taken into consideration”!

An example of this is also Israel’s peculiar use of the term “armed conflict short of war” or “low-intensity conflict” to describe the Palestinian intifada, even though it is a military term associated with the state’s limited military operations against groups classified as terrorist or smuggling and drug gangs, it is often called low-intensity conflicts in failed states that do not have an effective central political system. If we assume, for the sake of argument, that this term applies in this case, it lacks any firm legal framework, and it is not recognized in the texts of international humanitarian law. However, the Israeli legal machinery sought to present it as legal justification, and accordingly, it does not treat the Palestinian prisoners as prisoners of war, and they aren’t recognized as a legitimate fighting force.

Palestinian exceptionalism?

Noura Erekat also spoke in her book (2) about the difficulty of the international factor in the Palestinian cause. In all cases of liberation, we found an international alliance to fight for it, but in the Palestinian cause, we hardly find anyone defending the right of the Palestinians to defend themselves and to use force to determine their destiny – even though it is legally guaranteed in the principles of international law and repeated General Assembly resolutions. If a Palestinian uses the weapon, he is a terrorist without discussion, even if he adheres to the rules of the law of war “international humanitarian law.”

Here, the author gave other examples of successful liberation movements and tried to extrapolate the reasons for success, including the case of Namibia(3), which entered a war, the Namibians called it the Namibian Liberation War, in which the Namibian People’s Liberation Army fought the South African forces of the apartheid regime. The author believes that her success is based on three factors: First: The Namibians’ rejection of bilateral negotiations with racist South Africa – being the weakest party – and their insistence that the negotiations must be under the cover of the United Nations. Second, the Namibian armed struggle continued until the last moment of the agreement’s signing. Third: that the international system was not biased against them – as it is biased against the Palestinians. Moreover, the author compared the insistence of the Namibians on their struggle despite their progress in the negotiations, to the negotiations with the British mandate during the Great Revolution in the 1930s and until the publication of the White Paper, and she believes that once the Palestinians gave up the struggle, Britain soon failed to abide by its duties.

What is to be done?

Finally, the author wonders: Will the law free us? She believes that the answer is no, but also that Palestine cannot be free without it. In her opinion, what is required is that we search for strength papers and work to activate all the tools of law and work to make it adopt the story of the right holder. And she believes that the first step in that is to move away from the United States and search for a true international ally. She gave examples of Palestinian creativity that found solutions and made something out of nothing.

She believes that international law is not linked to lawyers only, as many people think. Here, she criticizes the method that has been approached by the International Criminal Court concerning Palestine and she believes that what is required should be invested in the media to gain support, not merely sending lawyers in uniform to win the case. And while she sees that the Palestinians should not wait for much from the International Criminal Court, she believes that there is no shortage of good Palestinian lawyers, but there is a need for a strong political movement to publicize their legal advocacy and benefit from their tactical gains.

Conclusion

“Justice for some” is an inevitable addition to the Palestinian library, and a rare legal register of the conflict from a Palestinian point of view, in a language crowded with writings dyed by the Israeli narrative. At the same time, it is a legal summary that can be used in the study of the relationship of politics to the law in general, and in how the law does not grow in a vacuum, but in an environment attracted by political interests.

International law, despite its faults, was undoubtedly a deterrent to many of the major violations that could have occurred more often

Certainly, it is possible to disagree with the author about some of what she went to. International law, despite its faults, was undoubtedly a deterrent to many of the major violations that could have occurred more often, and there is no doubt that Israel stopped at some borders concerning its wars on Gaza in the years 2009, 2012, and 2014, the reason behind that was considerations related to the extent of the destruction that is possible and “acceptable” internationally. The current context of the Palestinian issue in the ICC, and the leaks about Israel preparing a list of the names of officials who could be subjected to trial before the court, and the repeated files that Israel prepares to justify its wars and violations of international law are all indications of the extent of the challenge that the law represents in this regard. We say this while acknowledging that “law is politics,” as the author kindly said, and that the balance of power plays an important role in this area, but that balance of power can never justify a fixed war crime, or justify the occupation as a legal act.

In general, this book, written by a lawyer with great practical experience and great academic knowledge, comes to confirm that the Palestinians need to strive in activating the legal tools and dyeing the international law with their narrative based on rights, and not to let Israel and its lawyers play with the law as they please. Law – as Noura Erekat sees it in “Justice for Some” – is not sufficient to achieve justice, as she works in a political environment in which the strong control the weak, but the right holder is required to exert his power to impose his rights on the law.

—-

(1)- The author emphasized this idea in the conclusion of her book and gave examples mentioned in this context about the Palestinian struggle and how it affected the law.

(2)- The author spoke at length about this main point in the book, many of her lectures, and writings, which is the difficulty of the international factor and its contradiction with the Palestinian interest.

(3)-The author talked about the Namibian case several times in her book, but the analysis on the format mentioned here was in her book launching lecture.

* Hassan Imran is a writer and legal activist. He holds an LLM in international law (humanitarian law and human rights). He writes regularly for several outlets on issues related to international law and international politics. He has one co-authored book and is publishing another soon. To follow Imran’s work and views, check his profile on Twitter (@Hassan_Imran).