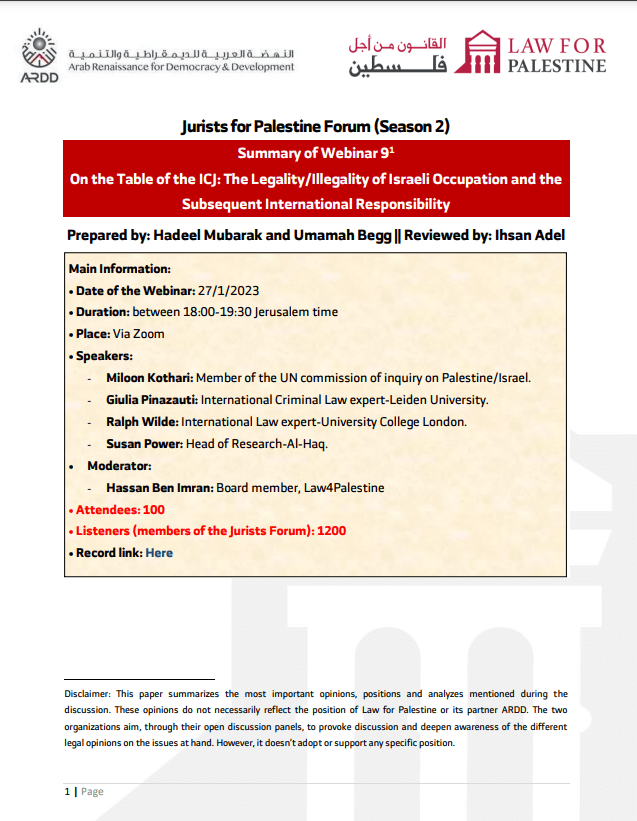

Jurists for Palestine Forum (Season 2)

Summary of Webinar 9[1]

On the Table of the ICJ: The Legality/Illegality of Israeli Occupation and the Subsequent International Responsibility

Prepared by: Hadeel Mubarak and Umamah Begg || Reviewed by: Ihsan Adel

To download this summary and transcript, kindly click here (pdf file)

Main Information:

|

Introduction

On December 30, 2022, the United Nations General Assembly requested that the International Court of Justice render an advisory opinion on the UN Charter, rules of IHL and IHRL, and the 2004 ICJ Wall advisory opinion on the following:

“(a) What are the legal consequences arising from the ongoing violation by Israel of the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination..

(b) How do the policies and practices of Israel referred to in paragraph … (a) above affect the legal status of the occupation, and what are the legal consequences .. for all States and the United Nations from this status”

The allegation of illegality is nothing new to the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and Gaza. The current UN Commission of Inquiry on Palestine/Israel (COI) recently finds that the Israeli occupation is unlawful under international law. A few years before that, the outgoing UN Special Rapporteur Prof. Michael Lynk established a four-point threshold for occupation to be deemed illegal; (i) the Occupying Power has annexed the territory, (ii) the occupation breaches the principle of temporariness, (iii) the Occupying Power fails to act in the best interests of the occupied population, and (iv) where an Occupying Power conducts the administration of territory in bad faith, by for example, building settlements. Prof. Ralph Wilde in a legal opinion (summarized here) argued that the Israeli occupation has crossed the threshold of legality arguing that the “existential illegality of the occupation arises out of the simple fact of the occupation as a system of control and domination without a valid legal basis.”

This webinar, organised by Law for Palestine and in partnership with ARDD, gathering international law experts and lawyers and NGOs directly involved and having a first-hand experience with the issue at hand, aims to:

- Discuss the UNJA resolution rendering upon the ICJ to deliver and advisory opinion on the Israeli occupation and the legal status in the OPT

- Discuss the legal consequences arising from the ongoing violation of the Palestinian’s right to self-determination and the legal consequences that arise for all states and the UN based on this status

- Discuss the findings of the UN Commission of Inquiry on the legal status of the Israeli occupation over the OPT

Speakers’ Discussion

Miloon Kothari

- There have been a number of commissions on Palestine over previous years, however this commission has some unique features allow it to make a small contribution to the resolution of the crisis:

- It is an open-ended mandate, meaning there is no end to the commission. It looks at root causes, and the historic reasoning behind the perpetuation of the conflict

- It is also mandated to look at the situation inside the green line.

- The thematic scope is broad, covering a range of human rights, humanitarian rights, criminal law, the establishment of legal accountability – including individual criminal responsibility.

- Two reports have been already published by the COI last year, one submitted to the Human Rights Council and the other to the General Assembly.

- First report reviewed the previous work done on Palestine. In conducting that review the COI noted that many findings and recommendations relevant to the underlying root causes were related to Palestinian entities and armed groups, but the vast majority were directed towards the state of Israel -confirming the asymmetrical nature of the conflict and dispelling the view that there are two parts parties on an equal footing, and reflecting the reality of one state occupying another.

- The report concluded that the state of Palestine is under perpetual occupation and there has been longstanding discrimination in both Israel and Palestine – which is one of the core root causes of the violence.

- The second report stated that the occupation is one of the core underlying root causes of conflict and that de jure and de facto annexation policies employed have become irreversible on the ground – whilst hiding behind ‘a fiction of temporariness’.

- The COI concluded that there were reasonable grounds to conclude that the occupation was now unlawful under international law due to its permanence, and that the de jure and de facto action taken to annex part of the land by Israel is with the intention to maintain permanent occupation

- In consideration of the facts in the first report, the COI noted that the ICJ had anticipated this scenario in its 2004 advisory opinion on the wall in which it laid out that the wall is establishing for a permanent and tantamount de facto annexation.

- It also found that coupled together establishment of settlements, the construction of the wall and its associated regime Israel was in breach of its obligation to respect the right of Palestinian people to self-determination.

- Thus, the COI recommended that an advisory opinion should be sought, which lays down legal consequences of other states stating that all states are under obligation to not recognise the illegal situation.

- Commission found that it was vital that the General Assembly asked the ICJ to revisit and expand on its 2004 advisory opinion, laying out the legal consequences of Israel’s refusal to end the occupation and respect Palestinian people’s right to self-determination, as well as make clear that the legal obligations of third States and the UN are what they are to ensure respect for international law.

Giulia Penazoti

- There are two statutory criteria that regulate the ICJ jurisdiction to render an advisory opinion, in the statute and the UN charter:

- First, the court can only reply to legal questions

- Second, only authorised bodies can submit a request

- Based on these criteria, it is clear that there is no question that the court has jurisdiction to give the requested opinion on the legality of the occupation:

- Under the UN charter, the General Assembly is authorised to request an opinion on any legal question – even if these relate to a deeply politicised situation – when the legal questions are framed as questions of law and presuppose an answer that is based on the application of international law.

- In regards to judicial propriety, the courts statute in article 65 states that the court has discretion [may] to decline to give an opinion that falls within its jurisdiction, however this is a discretionary power that is not regulated in the statute. In its past jurisprudence the court has said that it may decline to give an opinion to protect the integrity of its judicial function, but it also characterise its opinion as a participation in the activities of the UN. It said that in principle the court should not refuse such participation unless there are compelling reasons to do so. Until now, the court has only provided one such compelling reason: the lack of consent of an interest state that may render the giving of an advisory opinion incompatible with the courts judicial character.

- States increasingly used advisory proceedings to bring before the court contentious matters in situations where the other state doesn’t consent to the settlement of the dispute before the court.

- In the opinions that were issued in the past 20 years this happened in three out of four opinions, and in this case, Israel does not consent to the settlement of any disputes with Palestine for the ICJ.

- In some states, scholars and even members of the ICJ (including the president) had voiced concerns that this practice circumvents the principle of consent adjudication. and that the court should decline to give the opinion requested in some circumstances to protect the integrity of its judicial function

- How should the court deal with these arguments? The court has never declined to give an opinion based on considerations of judicial impropriety, even when the request is related to a pending dispute.

- Only on one occasion the court predecessor, the permanent court of international justice declined to issue an advisory opinion on a question that concerned “directly the main point of the controversy between the parties that were Finland and Russia”, and in this situation, the court stated that answering the question would be substantially equivalent to decide on a dispute between the parties. Also, however, in that case there were also other considerations at play: the circumstances of the case, giving the opinion would have required the consent and cooperation of both parties – because the question before the court was very much factual and Russia was neither a party to the statute of the permanent court nor a member of the League of Nations. It objected to the proceedings and refused to participate, so the court lacked factual elements to issue the opinion.

- The present court has never overruled this precedent, but always sought to distinguish it from the facts. This is unlikely to be a problem in the case of the opinion on the legality of the occupation. Israel, unlike Russia, is a UN member state and is a party to the court’s statute, so we can argue that it has given its consent in general to the exercise by the court of its advisory jurisdiction.

- The other consideration is that the court has progressively narrowed down the relevance of consent to advisory proceedings in two ways:

- First, the opinion requested doesn’t concern legal dispute:

- e. in Namibia, the fact that the court may have to pronounce on legal issues upon which the parties have radically divergent views doesn’t convert the case into a dispute.

- This was also repeated in Chagos, 2019 where the court held that it wasn’t dealing with a bilateral dispute about sovereignty, but with the question of colonisation – which is true but at the same time ruling on the legality of the decriminalisation process inevitably impacted on British sovereignty over Chagos. As such, if the court wasn’t dealing with a bilateral dispute in Chagos, it’s unlikely that it will reach a different conclusion in the opinion on the legality of the occupation.

- Secondly, the court has limited the relevance of consenting advisory proceedings by placing the dispute in their “broader framework”. Here the court looks at the object and the nature of the request

- First, the opinion requested doesn’t concern legal dispute:

- We can say that the request relates to questioning disputed between Israel and Palestine or between Israel and any other state, but it’s not upon a legal question that is actually pending between two or more states.

- The questions put to the court concern issues that are located in a broader frame of reference than the settlement of purely bilateral dispute. The court may look at the objects and the nature of the request (like the court said on its advisory opinion on the wall) as the subject matter is not only a bilateral matter between Israel and Palestine, given the UN preeminent responsibility towards the question of Palestine. In other cases the court looked at whether the opinion meant to guide the action of the UNGA or UNSC in the performance of their own functions.

- The request of the advisory opinion on the legality/ illegality of occupation, the subject matter of the request goes beyond a bilateral dispute because it prompts the court to examine the necessity and proportionality of the occupation under jus ad bellum and weather the conduct of Israeli authorities breaches relevant rules of international law including the right to self-determination in a way that affects the legal status of the occupied territory. Self-determination as put by the court crates erga omnes obligations for the entire international community, so this is not purely a bilateral matter.

- The court has jurisdiction to give the opinion requested and there are no compelling reasons why the court should decline the opinion requested.

- By replying to the request, the court not only remains faithful to the requirements of judicial character, but discharges its functions as the principal judicial organ of the United Nations.

- To conclude, what will the court say in answering the request and how far it will go?

Ralph Wilde

- The terms ‘legality’ or ‘illegality’ can refer to the existence of the occupation or its conduct, or both. However, existential legality or illegality can refer to the occupation simply by virtue of exercising control over the West Bank including east Jerusalem and Gaza, consequently preventing the Palestinian people from full and effective self-governance, constitutes a fundamental impediment to the realisation of the right of self-determination enjoyed by the Palestinian people in international law.

- The only basis such an impediment could be legally justified is according to the law on the use of force – the jus ad bellum.

- Israel’s argument to the right to self-defence in international law, which was used as a means to justify the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza in 1967, has not persisted. There has been no actual or immanent armed attack that justified the occupation as necessary and proportionate, as a means of self-defence

- The doctrine of preventative self-defence (which would justify the occupation as a means of stopping a threat from emerging) has no basis in international law.

- Neither UNSC 242 nor the Oslo Accords provide an alternative legal basis for the existence/continuation of the occupation. In fact, Oslo Accords violates international law because the PLO’s consent was coerced by the illegal use of force of occupation. Both conflicted with norms of a jus cogens status.

- There is no international law right to maintain the occupation pending a peace agreement, and/or as a means of creating facts on the ground that might give Israel advantage’s in relation to such an agreement and/or as a means of coercing the Palestinian people into agreeing a settlement to the situation that they would not accept otherwise.

- As such, there is no valid international law basis for the existence of the occupation. The occupation is therefore an unlawful use of force and aggression and a violation of the right of self-determination of the Palestinian people, and also a crime on an individual level for senior Israeli leaders.

- The occupation is existentially illegal and must end immediately.

- Legally, the requirement of termination is not contingent on particular circumstances being present, thus every day the occupation continues is a breach of international law.

- The existential illegality of the occupation arises out of this simple fact of the occupation as a system of control and domination without a valid legal basis. This is compounded by the occupation’s prolonged duration, its link to de jure and de facto annexation, and the egregious abuses perpetrated against the Palestinian people.

- The use of military force to annex territory is also an independent basis for existential illegality and is also a violation of international law on the use of force and so an aggression at both a state level and in terms of individual criminal responsibility.

- Any purported annexations are also without legal effect, because in international law Israel is not and cannot be sovereign over any parts of the West Bank or Gaza including East Jerusalem through the assertion of a claim to this effect based on the exercise of effective control enabled through the use of force, and in the absence of consent to such annexation freely given by the Palestinian people.

- In regards to the legality or illegality of the conduct of the occupation, there are multiple egregious breaches of the relevant areas of applicable international law. These are breaches at the level of the state of Israel and also in some cases individual crimes (war crimes, crimes against humanity, the crime of apartheid and the crime of torture).

- The occupation is thus illegal in both its existence and its conduct and in both cases this gives rise to both state and individual criminal responsibility.

- All the main areas of international law violated here (the prohibition on the use of force other than self defence, the right of self-determination, the prohibition of racial discrimination generally and apartheid in particular) are a subset of the protections in IHL that are violated (and in particular the prohibition of torture). These are all norms that have the special non-derogable jus cogen status.

- Jus cogens or non-derogable status is not a separate category of substantive international legal rules, but is a way of characterising certain rules and being of a special character when it comes to their interaction with other rules of international law.

Suzan Power:

- Article 14 of the ”Draft articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts” highlights that the international obligations on a state committing a continuing crime arise only for the period during which the act continues.

- This gives a good parameter for gauging acts which were originally lawful becoming unlawful overtime

- According to the International Law Commission commentary of the article 14 the simplest characterization of a continuing unlawful act is the unlawful occupation of the territory of another state, thus for example, saying that the occupation an unlawful aggression in 1967, consequences would arise from the continuation of an internationally unlawful act.

- Similarly one could wage in relation to a self-defense argument even if Israel original use of force was a legitimate act of self-defense:

- Israel continued belligerent occupation of the Palestinian territory for almost 56 years and decades after it concluded peace agreements with Egypt in 1973 and with Jordan in 1994, and also decades after the UNSC calls for its ending and withdrawal, highlights that the belligerent occupation really has exceeded all parameters of military and necessity and proportionality, and incurs state responsibility as an internationally wrongful act.

- There are important customary international law consequences that flow form the breach of an internationally wrongful act, these includes the obligation to cease that act, and offer appropriate assurances and guarantees of non-repetition.

- A state is responsible and obliged to make restitution, it should re-establish the situation that existed before the wrongful act was committed.

- For example: in the Namibia case, the International Court of Justice held that South Africa had an obligation to withdraw its administration from the territory of Namibia

- In the case of Israel, we could see recommendations to withdraw military administration from the territory.

- It is important to note that the UNGA has adopted numerous resolutions calling for Israel’s unconditional and total withdrawal, this means that withdrawal is not a subject of negotiation, but rather it is to be terminated completely because it is an internationally wrongful act.

- There are also consequences that arise for third States including that of non-recognition of the international wrongful act, as stated in article 41 (2) of the draft articles ‘No State shall recognize as lawful a situation created by a serious breach within the meaning of article 40, nor render aid or assistance in maintaining that situation”.’.

- Where the ICJ throughout its Advisory Opinion on the Wall considered the legal consequences arose for all states who were under an obligation not to recognize the situation which had arisen from the construction of the wall, and not to render aid or assistance in maintaining that situation and to cooperate with the view to putting an end to the alleged violations and to ensuring the reparations will be made.

- In the case of Namibia, the ICJ provided that third states obliged to abstain from entering into treaty relations with the occupying power, where it purports to act for the ousted occupied sovereign and also remove all diplomatic consular and special missions, both to the territory of the occupying power and the jurisdiction of the occupying power in the occupied territory, it also called for third states to abstain entering into economic and other forms of relationships or dealing with South Africa on behalf of, or concerning Namibia.

- The UNSC called upon all states to prevent imports or conduct any commercial industrial or public utility from an aggressor occupying power in relation to the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait

- In recent years there has also been countermeasures applied by third States and intergovernmental organisations – this is not specifically provided for in the draft articles but it is developing in terms of state practice

- For example: the EU responded with restrictive measures against Russia’s military attack against Ukraine with individual sanctions, economic sanctions, and diplomatic measures

- International responsibility of the UN, which has permanent responsibility with regard to the question of Palestine, and this responsibility is until the question is resolved in all its aspects in accordance with international law and relevant resolutions.

- Matters such as the resettlement into Palestine of returned Palestinian national’s maybe an issue that the ICJ addresses to the UNGA, and this would be for the completion of decolonization, and this would include calls for the cooperation of all states in this regard.

- Similar measures had been taken in the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait, where there was a high level coordinator appointed to report to the UN Security Council on the repatriation and return of Kuwaiti nationals and the return of Kuwaiti property. Recalling such situations is very important, noting that the UN Security Council resolution 2334 already urges without delay international and diplomatic efforts to end the Israeli occupation that began in 1967.

- We would hopefully see similar measures and obligations outlined in relation to Palestine, and this would be particularly important for issues around return and repatriation of property

- A finding on the status of occupation would provide legal clarity on the steps and the legal consequences for de-occupation and full decolonization

- In regards to Palestine, it’s important to reiterate its existential nature, and is therefore imperative that third states would fully commit to this process, and that the International Court of Justice also work towards advancing the calls of the Palestinian people for full self-determination and the right of return, and take all necessary steps to dismantle Israel’s military administration of the occupied territory

Comments and Q & A

Question1: Dr. Mutaz Qafisheh

- To Miloon: What ideas are currently on the table of the commission of inquiry for the future?

- Second question (to Julia / Ralph) Regarding the composition of the court or politics of the court. Can you predict what the court might say, and to which extent the court may go in regard to the question of legality and illegality?

- Third Question to Suzan) Regarding the states who voted against the establishment of the commission of inquiry and the referral of the case to the ICJ. Under the law of state responsibility, can they invoke their previous positions and therefor argue that they are not obliged to respect this opinion, and what could be the response to these states?

Panelist Responses:

Miloon Kothari

What’s on our table is the following,

- We have been holding a series of public hearings where the voices of Human Rights defenders that can be heard all over the world (these have been broadcasted live on UN television). We’ve held one series of hearings for the leaders of the civil Society organizations who are being labeled as terrorists; moreover, on the course of Sherin Abu Akleh case, we will continue to hold public hearings.

- We have called for submission of reports for one of our forthcoming reports which is going to be on the impact on civil society journalists, lawyers of the occupation.

- Regarding the topic of this discussion, we look forward to contributing if the ICJ desires to the deliberations on the matter – as a COI we know how best we can intervene if necessary – but we have made it clear that we would like the Court to layout what are legal consequences of Israel’s continued refusal to end the occupation, given that as we’ve been hearing the occupation must, under international law, be temporary in nature and the international prohibition on the acquisition of territory by force.

Giulia Pinazoti:

- I’ve not looked into the court composition to predict how the court may answer the request coming from the general assembly, but just by looking at who the members of the court are, this is an entirely different bench from the one that ruled on the wall advisory opinion in 2004. I am afraid there will be uncertainty about what the court will say until the last minute.

- The timing of the request is such that the court may not rush to rule on this request for an advisory opinion, so there is likely to be potentially further changes in the composition of the bench if this case is not herd until 2024.

- If we look at the current bench, we know how Judge Donaghue and Tomka voted in the Chagos advisory opinion – so that may be an opinion. However, with the new court it is very hard to predict. Some judges may be sympathetic, and will want the court to issue an opinion – but for the other members, it is very hard to say.

Suzan Power:

- We’ve seen similar pushback by third states before, like the pushback that occurred before the pre-trial in the ICC where there were a number of states who submitted amicus curiae submissions against the question – and it could be seen in this advisory opinion something similar where states are pushing back against the question, and submitting their positions on this. However, in terms of the advisory opinion, once it’s given would carry significant legal weight.

Question 2: Tayma: International Relations and Computer Science student

- First (to Suzan), How do you navigate such highly politicized organ of the UN with the only enforcement power being with the P5 of SC? What are the things we need to learn from the previous advisory opinions and maybe make better or use to have more impact in that matter?

- Second (to Ralph), What is the impact of illegality on the settlements in the West Bank? How would that advisory opinion affect the settlement position, which is already illegal in international law?

Panelist Responses:

Suzan Power:

- The question of enforcement is very significant because military administration itself has been considered de facto legal, and there has been no move to bring that military administration to end, the advisory opinion gives us the opportunity to change the discourse and states obligations to act in relation to international law, as every time we will be talking about the occupation we will be talking about bringing it as well as the apartheid to an end. It wont come to an end immediately, but it carries significant weight.

- All of this jurisprudence and these positions on Israel, and the obligation to bring the occupation and the apartheid to an end – this gives us a long-term strategy to dismantle the occupation and the apartheid regime.

- The end of the occupation will be probable a matter of politics but we need to have the tools at our disposal to ensure that states respect the obligations and to show that third states themselves have obligations to end the occupation.

Ralph Wilde:

- The consequence of the occupation being existentially illegal, is that the occupation itself should immediately be terminated, and the settlers and the settlements should be removed and dismantled – and that is an immediate requirement arising out of the existential illegality of the situation.

- A further related matter is the link between the existence of the settlers and the settlements, and any claim that Israel might have to use military force in self-defense, this does not have any legal basis for self-defense, and one of the main issues here is that the ongoing military control is understood in security terms, and not as a response to actual or imminent attacks but rather as preventative self-defense using force to stop a threat from emerging, and part of this, is using force as a means of protecting settlements, and settlers preventing a threat from emerging to them.

- The inadmissibility of the doctrine of preventative self-defense in international law does not only apply to the general occupation as a means of Isreal promoting its own security, but more specifically in Israel enabling the security of the settlers.

- There is sometimes a mistaken idea that because Human Rights Law applies extra-territory to Israel in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, that therefore somehow, settlers have (as right holders) the right to remain in the territory – and this is an entirely incorrect understanding of the meaning of Human Rights Law, which is context specific and therefore requires for its correct meaning in this context to be appreciated – the significance of the right to self-determination to be appreciated, and how that right coops completely different as between the Palestinian people in the West Bank and Gaza on the one hand, and Israeli settlers on the other.

- Self-determination is part of human rights law, as well as being part of general international law. It is paramount that any legal analysis of the situation that is done on a human right basis includes the human right to self-determination.

Miloon Kothari

- Times have changed from the last time the ICJ ruled on Palestine. The UN has to forward all credible information to the ICJ before the court deliberates on the matter, and therefore there is a lot of detailed information out there, and it would be difficult for the ICJ to ignore all of that, in addition to the situation on the ground being much worse. Times have changed, and it is likely we will get a strong advisory opinion.

Question 3:

- What about Jerusalem in light of this discussion? The status of Jerusalem in light of these findings?

Panelist Responses:

Miloon Kothari

- Regarding Jerusalem, we consider it as part of the occupied territory, and therefore, everything that applies to the West Bank would apply to East Jerusalem.

Question 4: Ihsan Adel

- First (to Ralph) In regards to the counter argument, we know that an occupation that begins as self-defense is lawful and remains so until a negotiated solution is reached.My question is about these expected arguments that can be brought to the Court to defend the legitimacy of the Israeli occupation.

- Second (to Giulia) Do you think that the question formula that was referred to the court by the UNGA allows it to deal with the issue of apartheid, as well as the issue of the Israeli occupation being a form of colonialism as was put by the UN special rapporteur in her last report?

Panelist Response:

Giulia Pinazoti:

- The question formula is broad enough that it would allow the court to touch on a wide array of legal issues, particularly in response to written and oral submissions that will be made to the participants

- Many states want to participate in the proceedings and make arguments about Israel being an apartheid regime and a colonial state, therefore it will be much harder for the court to ignore those arguments completely, even though those words are not expressly mentioned as it is phrased.

Ralph Wilde:

- Regarding the use of force as self-defence: This only permits force which is a response to an actual or immanent threat and where the force used -here is military occupation- is necessary and proportionate to that attack or imminent threat.

- It is possible to make a case that the ad bellum test was met at the stage where the occupation was introduced – but if it was not, then the occupation has been illegal from the beginning. Proceeding from the hypothetical basis that there was a lawful basis for introducing the occupation in 1967, some commentators seemed to suggest that provided it existed from that moment of introduction, the matter of legality in the law on the use of force has been resolved for not only that moment, but also the continued operation of the occupation, and no further analysis is needed as time moves forward. Therefore, the occupation can continue, without the occupation itself needing to meet any justificatory test – and it is left for the occupier to decide when they wish to end the occupation.

- A more common view is that there is a legal requirement to end the occupation (presumably because of the right of self-determination), but the test for when the end should come is different from the jus ad bellum test. Specifically, some have suggested that the test is the occupation can continue until there is a peace agreement. The risk that such a test could then enable an occupier to prolonged its occupation by failing to make good faith to pursue such an agreement – a tighter version of this approach is to say that an occupation is permitted to continue until reaching a peace agreement provided that the occupier is making all possible efforts to achieve that agreement.

- The requirement to meet the general ad bellum test is an ongoing one in any continuing use of force including a military occupation. However, commentators and policy makers overlook that the use of force requiring justification on this basis is not simply the initial period of invasion that proceeds and enables an occupation, it is also the operation of the occupation – since the conduct of an operation is itself a use of force. In consequence, the test remains on an ongoing basis, needing to establish an actual or an imminent threat of an armed attack, and that the type of forced used should be necessary and proportionate to the test. If the test is not met (which is the case here), then the occupation is illegal, even in the absence of a peace agreement. Whether or not a peace agreement has been reached, and whether or not the occupying state is making efforts to reach such an agreement, are not by themselves dispositive of whether the occupation is or is not legally justified.

Question 5:

- (To Giulia) With reference to the court declining cases, were there any political pressure a factor in this case such as the ICC de-prioritization of the case of Palestine?

Panelist Responses:

Giulia Pinazoti:

- The PICJ declined a case in 1923, and it’s hard to tell weather political pressure then was a factor or not, however, there were legal grounds where the Court cited in its opinion for its refusal to exercise its discretion to give the opinion requested, and, in that case, Russia was not a state member to the League of Nations so they had a pretty strong argument to decline to give the opinion requested.

Question 6,

- (To Suzan) What is the role of the PA into following up on this advisory opinion and the other one on the wall?

- How is your work as an advisor to Al-Haq restricted or not due to the last decision on having those human rights organisations marked as terrorists?

Panelist Responses:

Suzan Power:

- In relation to role of the PA, at the GA we had the PA as a member state observer, and also other states present the resolution at the special committee on decolonisation. This was an active role of the PA, and this engagement will continue with submissions as the advisory opinion progresses. However, there is significant retaliation against the PA for advancing the advisory opinon, and there has been pushback by Israel with the suspension of revenues to the PA as a collective punishment measure (alongside retaliation against human rights and civil rights organisation who have been conducting advocacy on this issue).

- Al-Haq as well as human rights organisations were very active on the lead-up to the GA resolution, in doing advocacy with third states to push for support for the advisory opinion.

- In terms of the designation of Al-Haq as an alleged terror organization under Israel’s Counter Terrorism law, these are grounds which are unsubstansatied and have been decried as not credible and not based on any evidence by states of the EU and many third states. There has been overwhelming support from other civil society organisations as well. There is of course a chilling affect, and a dagger hanging over our work with the consequences of that. Only a few months ago our general director, and the general director of Defense for Children International were threatened with arbitrary arrest and detention for continuing with the human rights work.

- The more we advance our work at the COI and the advisory opinions levels, and around the ICC, we become more susceptible to attacks and raids by Israel. However we remain absolutely committed to our mandate to try every legal avenue and all peaceful and legitimate means, and human rights avenue’s for the full realization of the self-determination of the Palestinian people as well as their right of return, and the dismantling of the apartheid regime and the illegal occupation.

_END_

1. Disclaimer: This paper summarizes the most important opinions, positions and analyzes mentioned during the discussion. These opinions do not necessarily reflect the position of Law for Palestine or its partner ARDD. The two organizations aim, through their open discussion panels, to provoke discussion and deepen awareness of the different legal opinions on the issues at hand. However, it doesn’t adopt or support any specific position.