One Year for International Law Rising in Ukraine and Falling in Palestine: Beyond the Blame-Game

Written by: Hassan Ben Imran, Ihsan Adel, Wadea Alarabeed

* To read this article in a printable pdf version, click here

Introduction

“Imagine as if that what is happening in Ukraine is happening in Palestine instead, and that Russia is the United States!”. With these ironic -and distressing- words commented the Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov highlighting the Western double standards in dealing with the Ukraine war compared to other similar cases. As if to say, why blame us for our aggression when you do not blame your allies for theirs?

Exactly one year ago, on February 24th, Russia declared the launch of a wide military operation to take over Ukrainian territories, with the hostilities still ongoing. This military operation were faced with a barrage of European and American condemnations, followed by a slew of economic sanctions against the Russian Federation, followed by armament and support for the Ukrainian military and recalling Ukrainian right to self-defense under international law along with the immediate termination to illegal occupation. European and North American law associations were quite quick to condemn Russian actions, abandoning their old policy of staying out of politically sensitive developments; such as the unilateral American invasion of Iraq outside UN collective security system.

To have some context: both Palestine and Ukraine are clearly under occupation and have witnessed various international crimes, including war crimes and crimes against humanity as argued by many authoritative bodies and jurists. This requires greater efforts from the international community to achieve justice and equally enforce international law. Palestine, however, has been under the Israeli occupation since 1967, with almost a countless number of UN resolutions, including Security Council Resolutions No. 242 and 2334 of 2016, referring to Palestine as an occupied territory subject to international humanitarian and human rights law and demanding an end to the Israeli occupation, or at least its settlement activities in the OPT. Needless to say, these resolutions seemed to have skipped Israel and its powerful allies’ attention, denying the Palestinian rights to self-determination or self-defense.

This article sheds the light on the notorious double standards in Western countries voting patterns in the UNGA and how it negatively affects the while regime of international law. Then it discusses the way forward for Palestine to overcome the behavioral and structural injustices inflicted on its people.

“All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others”

A quick comparison of Western states’ votes in the United Nations General Assembly in the Ukrainian and Palestinian cases demonstrates that George Orwell’s remark was not just witticism.

According to table 1 below, there is a vast and incomprehensible discrepancy between the vote of the major Western countries (namely the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Spain and Italy) in the case of Ukraine versus Palestine.

As they are all condemning the Russian invasion and supporting the Ukrainian sovereignty and territorial integrity while unanimously shielding Israel from legal accountability (whether by voting against, or by renouncing responsibility by abstaining) before the International Court of Justice, all of which voted in favor of its establishment when the United Nations was founded

Table 1: The vote about Ukraine

According to table 2 below, remarkably, several of the afore-mentioned seven major countries voted unanimously in favor of Ukraine, while none voted in favor of the Palestine resolution. In the best-case scenarios, some of them abstained (Spain, France, and the United Kingdom which initially abstained but later decided to vote against in the subsequent vote; see table 3). Notably, Ukraine initially voted in favor of the Palestine resolution (in the Fourth Committee session), but then did not attend the following session (UNGA session).

Table 2: First voting session in November on referring the case to the International Court of Justicex§

Table 3: The second vote on ICJ-Palestine

Although some European states’ position improved noticeably (or arguably ‘de-deteriorated’), where they switched positions from voting against to abstaining, it is still surprising that countries hosting international institutions have abstained.

The Netherlands, which hosts the headquarters of the International Court of Justice (about which the vote is taking place) and the International Criminal Court, abstained instead of voting in favor of the Court’s mandate, and so did Switzerland that hosts the headquarters of the Human Rights Council. Further, Norway and Sweden, holding a more progressive stance towards the issue and international institutions in general than the traditional European one, also abstained. Only four of the Western countries enlisted in (Table 4) were consistent in their voting pattern.

The Netherlands, which hosts the headquarters of the International Court of Justice (about which the vote is taking place) and the International Criminal Court, abstained instead of voting in favor of the Court’s mandate, and so did Switzerland that hosts the headquarters of the Human Rights Council

The following Table 4 summarizes the paradox of a number of the more involved Western states’ voting pattern in both cases: Ukraine and Palestine.

Table 4: Voting Pattern of some Western states in both Palestine and Ukraine.

| Country | UNGA Ukraine vote (October (2022) | UNGA initial Palestine-ICJ vote (November 2022) | UNGA 2nd Palestine-ICJ vote

(December 2022) |

|

| 1 | USA | For | Against | Against |

| 2 | Canada | For | Against | Against |

| 3 | UK | For | Abstained | Against |

| 4 | Germany | For | Against | Against |

| 5 | France | For | Abstained | Abstained |

| 6 | Spain | For | Abstained | Abstained |

| 7 | Italy | For | Against | Against |

| 8 | Poland | For | For | For |

| 9 | Portugal | For | For | For |

| 10 | Netherlands | For | Abstained | Abstained |

| 11 | Belgium | For | For | For |

| 12 | Austria | For | Against | Against |

| 13 | Switzerland | For | Abstained | Abstained |

| 14 | Norway | For | Abstained | Abstained |

| 15 | Sweden | For | Abstained | Abstained |

| 16 | Finland | For | Abstained | Abstained |

| 17 | Denmark | For | Abstained | Abstained |

| 18 | Ukraine | For | For | Absent |

| 19 | Ireland | For | For | For |

| 20 | Australia | For | Against | Against |

In contrast, considering the voting pattern of a number of states with relative influence outside Europe and North America, there is a remarkable relative harmony in voting between the Ukrainian and Palestinian cases which invites us to assume that their vote was rather principle-based than opportunistic –excepting from this, in the case of Ukraine, states that are either directly or semi-directly involved in, or affected by, the consequences of the Russian war against Ukraine, such as Russia itself, China, India and Pakistan.

Table 5: Voting pattern of other states in both cases:

| Country | UNGA Ukraine vote (October 2022) | UNGA initial Palestine-ICJ vote (November 2022) | UNGA 2nd Palestine-ICJ vote

(December 2022) |

|

| 1 | Brazil | For | For | Abstained |

| 2 | Russia | Against | For | For |

| 3 | India | Abstained | Abstained | Abstained |

| 4 | China | Abstained | For | For |

| 5 | South Africa | Abstained | For | For |

| 6 | Turkey | For | For | For |

| 7 | Indonesia | For | For | For |

| 8 | Malaysia | For | For | For |

| 9 | Pakistan | Abstained | For | For |

| 10 | Nigeria | For | For | For |

| 11 | Alegria | Abstained | For | For |

| 12 | Morocco | For | For | For |

| 13 | Egypt | For | For | For |

| 14 | Senegal | For | For | For |

| 15 | Cameroon | Absent | Abstained | Abstained |

| 16 | Argentina | For | For | For |

| 17 | Chile | For | For | For |

| 18 | Mexico | For | For | For |

| 19 | Tunisia | For | For | For |

| 20 | Saudi Arabia | For | For | For |

| 21 | South Korea | For | Abstained | Abstained |

| 22 | Japan | For | Abstained | Abstained |

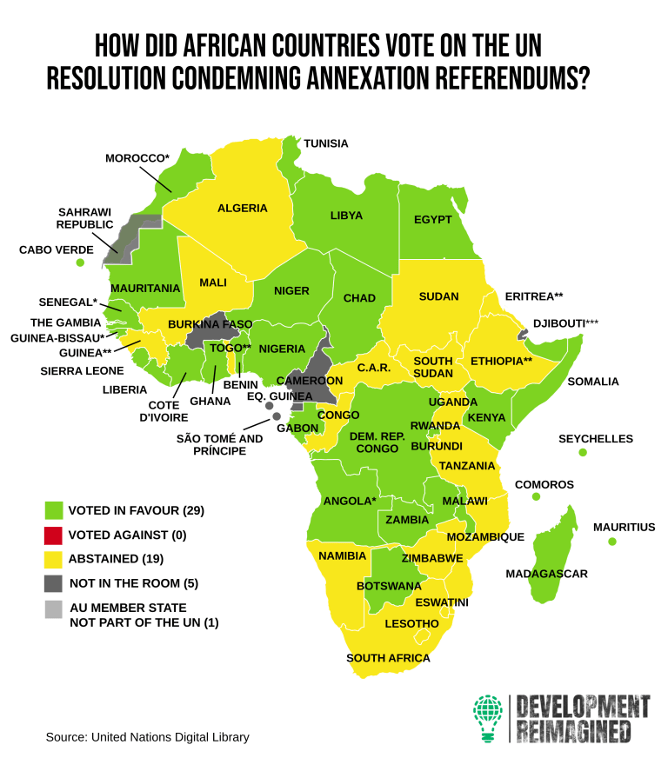

Taking a look at the African states’ voting pattern with regards to both votes, it is quite noticeable that none voted against the Ukraine resolution back in October 2022, as shown below in (Chart 1). The vote on Palestine was quite similar with only Kenya and Liberia voting against. Here it is worth mentioning the African countries’ rich heritage and contribution to the international legal regime in the post-colonial era; such as the first addition protocol and the legalization of liberation movements. This is a role that is still very needed right now.

Chart 1: African countries’ voting on Ukraine’s October resolution.

A general review of these tables reinforces the serious assumption that the states in general, but mainly the major Western countries (and particularly the afore-mentioned big seven) see international law and its institutions as a tool to employ in their foreign policy, rather than as a law that must be upheld.

The hand of justice: strikes in Ukraine, observes in Palestine

“Justice delayed is justice denied”: A viewpoint mirrored in major Western countries’ attitudes toward Ukraine.

Soon after Russia launched its war on Ukraine, US President Joe Biden acknowledged that Russia’s attacks on Ukraine constituted war crimes and crimes against humanity, without waiting for an objective investigation. The Canadian Prime Minister considered it “’Absolutely right’ to call Russia’s actions in Ukraine a genocide”, while Belgium supported the conclusion that what Russia is committing constitutes a war crime. Similarly, Olaf Scholz, the chancellor of Germany condemned Russia.

In contrast, it seems that the hand of justice concerned with Palestine is suffering from essential tremor disorder.

Unlike Russia, Israel has never been sanctioned, or at least tangibly pressured, neither by European states nor by the United States to end its settlement expansion, let go of its occupation. This is despite the wide condemnation by multiple international organizations, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty international, Israeli rights groups. Add to that the multiple of international resolutions and UN commissions of inquiry concluding that the Israeli occupation committed war crimes and crimes against humanity in the OPT. The US and several European states hardly condemned Israeli actions, no one talk about aggression or Apartheid, and in many cases, they provided Israel with military and financial support. This includes the prominent example of US military support, which is estimated to be 3.8 billion USD per year between 2017 and 2028.

It seems that the hand of justice concerned with Palestine is suffering from essential tremor disorder

Meanwhile, a few days following the launch of the Russian military operations in Ukraine, both the European Union countries and the United States almost immediately, called upon the ICC to investigate the situation in Ukraine; accordingly, the office of the prosecutor opened an investigation on March 2, 2022 regarding alleged crimes committed in the context of situation in Ukraine since 21 November 2013. The decision to open the investigation was made in response to a request from over 39 states, including all European Union member states, Australia, Canada, Iceland, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom, which led the ICC Prosecutor, Karim Khan, to accept the request without any delay or observations. He visited Ukraine twice in less than a year, while only recently he announced his ‘intention’ to visit Palestine; Palestine first approached the Court in 2009 and it took it 12 years to declare jurisdiction over the OPT.

Political pressure, mainly by the United States, worked to obstruct the investigation of the Palestine case and to protect Israel before the Court. From 2018 to 2020, the Trump administration worked diligently to undermine the Court’s efforts to advance its investigations, including issuing an executive order in June 2020 that imposed sanctions, including bank account suspension and visa cancellation, against former ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda and Phakiso Mochochoko.

Even after the new US administration, led by President Biden, canceled President Trump’s executive order targeting court employees, it stated that it is “still opposing the procedures of the International Criminal Court in the Afghan and Palestinian situations” while offering assistance to the Court in the Ukrainian case!

Former German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s administration also submitted to the International Criminal Court in February 2020 trying to convince the Prosecutor that the Court’s does not have jurisdiction over the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Seven countries, of which five are Western, went so far as to challenge the ICC’s jurisdiction, claiming that the ICC lacks the jurisdiction to investigate Israeli war crimes against Palestinians; namely, Czech Republic, Austria, Australia, Hungary, Germany, Brazil (under the former President Bolsonaro Administration) and Uganda.

Perhaps assuming that international law is immediately enforced only when it comes to a country friendly with the great powers, particularly the afore-mentioned big seven Western states, is correct. This is reflected in the former British PM Boris Johnson’s statement, indicating that his government opposes an international criminal court investigation into alleged war crimes in the Israeli-occupied territories adding that “Israel is not a party to the Statute of Rome and Palestine is not a sovereign state” and that “this investigation gives the impression of being a partial and prejudicial attack on a friend and ally of the UK.” It is worth mentioning that Russia now is not a party to the Rome Statute, so will the UK still stand against the ICC investigation in Ukraine too? We know the answer.

Russia’s declaration of war was immediately followed by massive mobilization of resources and mechanisms to facilitate international accountability for Russia’s occupation of Ukraine, including the International Court of Justice and the European Court of Human Rights. On March 18, 2022, the International Court of Justice issued a provisional measure in this regard, less than two weeks after Ukraine had submitted an application to the Court in March 7, 2022 demanding that the Russian Federation stops the war and ceases military activities in Ukraine. In this context, the European Court of Human Rights has issued provisional measures calling on Russia to “refrain from military attacks against civilians and civilian objects” as well as other violations of international humanitarian law.

This high level of enthusiasm – that is absolutely justified and needed in the Ukrainian case- prompted Josep Borrell, the European Union High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, to point out the double standards in the way the EU dealt with both Ukraine and Palestine.

Palestinian exceptionalism versus Ukrainian exceptionalism!

It is unfortunate that the positive and enthusiastic atmosphere for justice in Ukraine was an exception not the rule. It is also regrettable that Palestine is not just excluded from that exception but in fact an exception in itself; in the sense of the extreme marginalization of international law and the silencing of voices advocating for Palestinian rights. Supporting Palestinian rights is an enough reason to be gaslighted with the antisemitism label as per the IHRA definition, and Anti-Palestinian Racism is on the rise; mainly in Israel and the West.

It is also regrettable that Palestine is not just excluded from that exception but in fact an exception in itself; in the sense of the extreme marginalization of international law and the silencing of voices advocating for Palestinian rights

It is argued that marginalizing the Palestinian case started as soon as Palestine was first under the British Mandate. As Ardi Imseis put it, the mandatory regime had created a pattern where international law is to be marginalized through the “hegemonic/subaltern” dichotomy inherent in the rule by law. It was an instrument to internationalize the subordinate legal status of the colonies at the global level, consequently producing what he termed as the international legal subalternity. The American-Palestinian lawyer Noura Erakat supported this argument in her book “Justice for Some” arguing that the “sovereign exception” marking Palestine as the site of Jewish settlement engendered a special legal arrangement that justified the legal erasure of the Palestinian political community. This regime, together with three decades of British imperial sponsorship, enabled Israel to assert its Zionist-Jewish settler sovereignty by force over 78% of Mandate Palestine in 1948, along with Syria’s Golan Heights, resulting in the marginalization of the law in Palestine and the creation of a new law tailored according to Israel’s needs.

We also recall the constant pressure to avoid labeling Israel’s regime as apartheid. Despite the fact that this regime was established as soon as the State of Israel came into existence and has been entrenched over the years of occupation after 1967, this discourse has only recently gained traction among respected human rights organizations. In fact, as a result to ESCWA attempting to issue a legal report using the term apartheid, Rima Khalaf, the Executive Secretary of ESCWA-West Asia, was put under immense pressure which led to her resignation and then removing the report from ESCWA’s website.

More recently, the European Union’s foreign policy chief, Josep Borrell, stated that the term apartheid is “inappropriate” to describe Israel, highlighting their adoption of the IHRA definition of anti-Semitism; a highly criticized definition by the Holocaust and Jewish studies’ experts due to it associating criticism of the State of Israel with anti-Semitism; specifically describing Israel as racist. Add to this the UN Security Council obstruction of the passage or implementation of several resolutions, as well as the unjustified slow pace of work by the International Criminal Court in the Palestinian case.

Whom to blame? International law, states, or not blame at all?

Abd El-Razzak El-Sanhuri; a renowned jurist who had a major part in shaping the Egyptian Civil Code, once said: “It is only among the equally strong or the equally weak that law rules; for if power is imbalanced, power becomes the law!”

It is no secret that this perspective is dominant among pro-Palestinian legal and political circles. Many believe that law, in light of the current absence of a balance of power, cannot serve justice. They believe that the very foundations of the current regime of international law (both treaties and institutions) are a proof of that; the UNSC veto power, the fact that most treaties were drafted and signed mainly by Western states, many of whom were colonizing “the rest” …etc

On the other side, Israel invests heavily in its legal capacities, with the help of its allies. For instance, a look at their submissions to the ICC or any international treaty body, and their post-Gaza-wars legal reports, give us a hint for how invested they are in the ‘law industry’, trying to mask its crimes with a legal facade. While, established judges and legal authorities would not fall for their arguments, no one can deny the very solid argumentation skills demonstrated.

Palestine and its allies have not fully and systematically pursued all the legal options. Pro-Palestinian jurists have been speaking of apartheid for decades, but only recently it was legally well-framed with B’tselem, HRW and Amnesty issuing their reports. Same applies for almost every aspect of the issue. One reason for that is the passive attitude towards international law. It is time we do what it is in our hand and leave fixing the international legal regime to a time when it is not merely a mental exercise.

Incidents where the international law regime upheld Palestinian rights are plenty. Palestine managed to join the ICC and become a party to its Rome Statute; despite Palestine being under military occupation. Another example is the current ICJ advisory opinion and the previous 2018 ICJ case against the US for relocating its embassy to Jerusalem; which was temporarily suspended by Palestine and if activated could lead to a binding decision against the US. Moreover, the PLO in 1988, despite not being officially recognized as a state by neither the UN or US then, managed (through the UN) to get an ICJ judgement in 1988 demanding the US to allow the PLO mission to the UN in New York to operate despite the US Anti-Terrorism Act. In 2019, the European Court of Justice ruled that products produced in the Israeli settlements in the OPT to be labeled, despite being too little and short of being called a sanction, was a positive step that could be built on. Other examples include the Rome District Court ruling, and the judicial failure to crackdown on the BDS movement and the list goes on and on. We are aware that most of these battles should have not been there in the first place; for why would Palestinians have to justify their pursuit of their legally enshrined rights? However, considering the extremely imbalanced international order we live in, these could be regarded as victories.

The Boycott Sanctions and Divestment movement (BDS), being based on international law, is a clear proof that law can push to serve justice, or more accurately a part of it. Israeli PM Netanyahu once compared the BDS to Iran; both being equally a “strategic threat”. In 2015, the very important Israeli National Security conference, known as the Herzliya Conference, listed the BDS on the top strategic threats next to Iran’s nuclear activities.

Following the legal victory, and together with the political and on-the-ground struggle, Namibia rose victorious. Just like Namibia, Palestine can be another ‘exception’.

We believe that just like in Namibia, law can make a difference. Namibia was under occupation by the Apartheid South Africa, and that occupation was supported by several Western countries -mainly the US. The ICJ issued an advisory opinion in 1970, widely known as the Namibia exception, labeling the occupation as illegal and demanding that South Africa withdraws from Namibian territories. Following the legal victory, and together with the political and on-the-ground struggle, Namibia rose victorious. Just like Namibia, Palestine can be another ‘exception’.

Just like Palestine, International law is a victim of colonialism. But here we are not trying to prove whether the problem is the international law regime or the states that are employing and undermining it. Here we are trying to say that passivism would lead us nowhere. Is the international legal regime flawed? Absolutely. Are we better off without it? Absolutely not.

Here we call upon the victims and their lawyers and representatives to uphold their duty to activate the international legal mechanisms and fight against the employment of international law for states’ interests.

To conclude, as demonstrated above, the recent UNGA votes revealed the enormity of the discrepancy, especially that both votes were very close in time. This brought us back once again to the same conclusions of political realism that international law is not enforced or called for, unless it serves the interests of the major powers that have the ability to influence the course of its implementation.

However, this is not a call for passivism, but rather for increasing the legal efforts to uphold the law; for the sake of the victims who need protection against major powers’ behavior undermining international law with their jungle-law-like approach. As demonstrated above, it worked once, and it can work again!

* Law for Palestine bears no responsibility for the content of the articles published on its website. The views and opinions expressed in these articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Organisation. All writers are encouraged to freely and openly exchange their views and enrich existing debates based on mutual respect.

Tags: One Year for International Law Rising in Ukraine and Falling in Palestine: Beyond the Blame-Game